This analysis is the first in a series dedicated to selected movements from Bernard Parmegiani’s suite De Natura Sonorum (1975). These reflections stem from personal research developed over the years with the aim of better interpreting this milestone of acousmatic music, especially in the context of live performance on the acousmonium. The analyses presented on this website have been refined and adapted through repeated use in various workshops on acousmatic practice, interpretation, and musical analysis since 2010.

At first listen, it is impossible not to think of another piece based on a single-pitch: Luciano Berio’s Sequenza VII for oboe, which revolves around a pedal B. In Berio’s work, the oboist performs over a sustained B, held by a different sound source (e. g. an oscillator), creating a tonal reference for the entire piece. Everything the oboist plays relates back to this latent tonic.

Berio’s choice of B is rooted in the organological characteristics of the oboe; it is perhaps the note that allows for the greatest variety of timbral modifications, as there are multiple fingerings that can produce subtle variations in both tone color and intonation of this pitch on the oboe. By locking the pitch material on this single pedal, the listener’s attention is not distracted by melodic activity and focuses entirely to the micro-variations in timbre created by these different fingerings and techniques.

As the oboist begins to explore pitches other than B, the piece takes on a new direction, expanding into the realm of pitch variation. This search for latent polyphony naturally leads to the exploration of multiphonics — a way to produce sort of “chords” with a monodic instrument such as the oboe. In fact, there is a clear climactic section in Sequenza VII where multiphonics dominate, marking a peak in the spectral saturation of the oboe’s sound. As we will see in a bit, this kind of spectral saturation also occurs in Parmegiani’s Accidents/Harmoniques.

Although some resemblances between Accidents/Harmoniques and Berio’s Sequenza VII is striking, I reached out to Parmegiani’s former assistant, Marco Marini, to ask whether there was any known influence. According to his conversation with Claude-Anne (Parmegiani’s widow) and Maxime Barthélemy, there is no written indication in Parmegiani’s notebooks suggesting any connection between the two works. Claude-Anne noted that while Parmegiani did listen to a wide range of contemporary composers, including Berio, he primarily did so to avoid repeating ideas that had already been explored. Thus, while one might identify interesting correspondences between the two pieces, there is no evidence that Sequenza VII directly influenced Accidents/Harmoniques. As Marco Marini states, however, Parmegiani does discuss his approach to working with orchestral extracts and his broader concept of “musique” in the book L’Envers d’une œuvre, written by Philippe Mion, Jean-Jacques Nattiez, and Jean-Christophe Thomas, something that may lead us to think about a further resemblance between some more collage-based works by Parmegiani (Musico-Picassa, Pop’eclectic, …) and Berio’s third movement of Sinfonia, to name the most representative; it should be also noted that the third movement of De natura sonorum, Géologie Sonore, also includes fragments of orchestral origin, as declared by the composer himself.

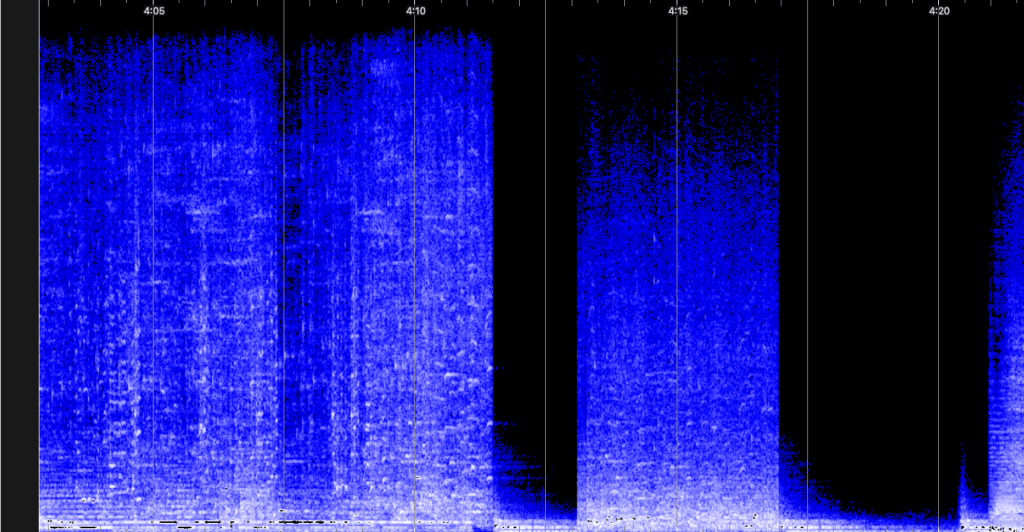

Looking at the sonogram of Accidents/Harmoniques, one can already discern the two fundamental dimensions of the piece: one horizontal and one vertical. The horizontal dimension is represented by the pedal tone (A, 440 Hz), which, in its first appearance, is a sound with very limited harmonic content, almost as pure as a sine wave. This static sound is interrupted by other elements, which diverge in various ways from the coherence of the pedal tone. Some of these interruptions retain a strong presence of the pivotal A frequency, while others are spectrally and behaviorally different: some feature pronounced attacks, others develop through glissandi, or have percussive characteristics. Thus, while the pedal tone (Element 1) is initially very static and restrained, it contrasts sharply with these interruptions (Element 2), which can be described as vertical due to their timbral complexity and noisy tendencies – and to their visual aspect on the sonogram.

At the beginning, Element 1 requires a certain time to be set as the main character — it occupies significantly more time than it does later in the piece. Element 2, on the other hand, is initially sporadic, perceived as a disturbance or noise disrupting the continuous and coherent presence of Element 1. However, from its second occurrence onwards, it becomes apparent that Element 1 is subtly changing: it begins to exhibit an allure (or vibrato), a slight perturbation that hints at its future trajectory. Vibrato can be conceptually thought as nothing else than a low-rate modulation of frequency or amplitude, basically the first step of a spectral saturation. This initially subtle perturbation foreshadows the eventual integration of Element 1 and Element 2: the pedal tone gradually expands spectrally, incorporating more and more harmonic content with each interruption by Element 2, as if the latter injects some of his essence into the former. This process of spectral enrichment gradually transforms Element 1 over time, until it evolves into material that closely resembles white noise rather than the pure tone of its origin.

The initial vibrato of Element 1 also introduces a sense of rhythm or pulsation. This pulsation, as an embryo of a more dense rhythmic articulation, can be interpreted as prefiguring the slow accumulation of the vertical material (Element 2), until the appearance of a granular quality. As the piece progresses, Element 2 becomes increasingly dense in time and in frequency/spectrum, a transformation clearly visible in the sonogram.

By the time the piece reaches the 4’10” mark, Element 1 and Element 2 are no longer distinct entities but have fused into a hybrid material which, resulting from an interaction between horizontal and vertical matter, inherits characteristics of both: it’s persistent over time, like Element 1, but it’s also rich spectrally, like Element 2. Its granular quality is particularly evident, as it suggests a continuous succession of condensed attacks within a rich and evolving timbral framework, resembling a sort of burning material.

As this hybrid material reaches its peak (around 4’10”), the piece undergoes a sudden and dramatic transformation, akin to a sudden chemical reaction. All internal articulations of the sound are stripped away, leaving only an alternation between two extreme states: bursts of noise (nearly petrified white noise) and silence. This stark juxtaposition between the totality of audible frequencies and their complete absence reflects, transfigured, the initial dualism of the piece: the horizontal (pure) and vertical (rich) dimensions have now crystallized into a binary opposition between noise and silence — an even more primal dichotomy.

The journey from pure sine tones to noise places Accidents/Harmoniques as a bridge within the cycle of De Natura Sonorum. It connects the first piece, Incidences/Résonances, composed of nearly pure tones, with the third, Géologie Sonore, which Parmegiani describes as constructed from layers of spectrally dense sounds derived from radio samples and orchestral recordings; layers which are meticulously filtered and superimposed, creating textures of remarkable complexity. This overarching progression—from purity to density—is mirrored in the microcosm of Accidents/Harmoniques, encapsulating Parmegiani’s exploration of sound as a dynamic interplay of opposites.

Pingback: Étude élastique – Compositional analysis | Alessandro Perini